Information Possibly Outdated

The information presented on this page was originally released on December 9, 2016. It may not be outdated, but please search our site for more current information. If you plan to quote or reference this information in a publication, please check with the Extension specialist or author before proceeding.

Deer tracking begins before leaving stands

RAYMOND, Miss. -- Woodsmanship and stewardship are two characteristics of all successful deer hunters as they track down injured deer.

The initial impulse most hunters have after taking a shot is to bail out of the stand and immediately look for their target. Depending on where the animal was hit, this hasty action could be a terrible mistake. Attempting to trail a deer prematurely can spook the deer even more and make locating it more difficult, if not impossible.

Although trailing a wounded deer is more of an art than a science, anyone can become proficient at it with careful planning before, during and after the shot. Establishing a basic routine can make tracking much easier. Hunters must pay close attention to the smallest details.

According to two Magnolia State outfitters, the first step in blood trailing a mortally wounded deer is a giant one. Hunters should always take this step before they climb down from the stand.

Robert Clay, a veteran deer guide in the lower Mississippi Delta, instructs his hunters to stay put and take careful inventory of the events that unfold following the shot.

“The first thing we tell our hunters is to remain in the stand immediately after the shot,” Clay said. “It is important that they pinpoint the exact spot the deer left the field and pay close attention to what it did. After making these mental notes, they can then get down and go mark the spot with flagging ribbon so we know exactly where to start.”

Jimmy Riley, manager and head guide for Giles Island Hunting Club in Natchez, has blood trailed many whitetails. He wants his clients to pay close attention to how the deer reacts to the shot. Does it hump up in the back? Does it kick out its hind legs? Does it leap into the air or drop down on all fours before leaving?

“The kind of blood I find helps me fill in the blanks when it comes to shot placement. Red, frothy blood indicates a well-placed shot through the heart or lungs and a deer that won’t go very far. Dark blood is good if it’s a liver shot, but most of the time it is indicative of a gut shot or a shot in one of the deer’s extremities,” Riley said.

Both guides agree that patience is critical in recovering a wounded deer. Hunters need to wait a certain period of time to allow the animal to bed down, stiffen up and die. Rushing in too quickly may result in rousing a wounded deer from its hiding place and unnecessarily extending the search.

“I prefer to wait at least an hour,” Clay said. “If there are indications of a poorly placed shot, I may even wait until the next day to begin blood trailing the deer.”

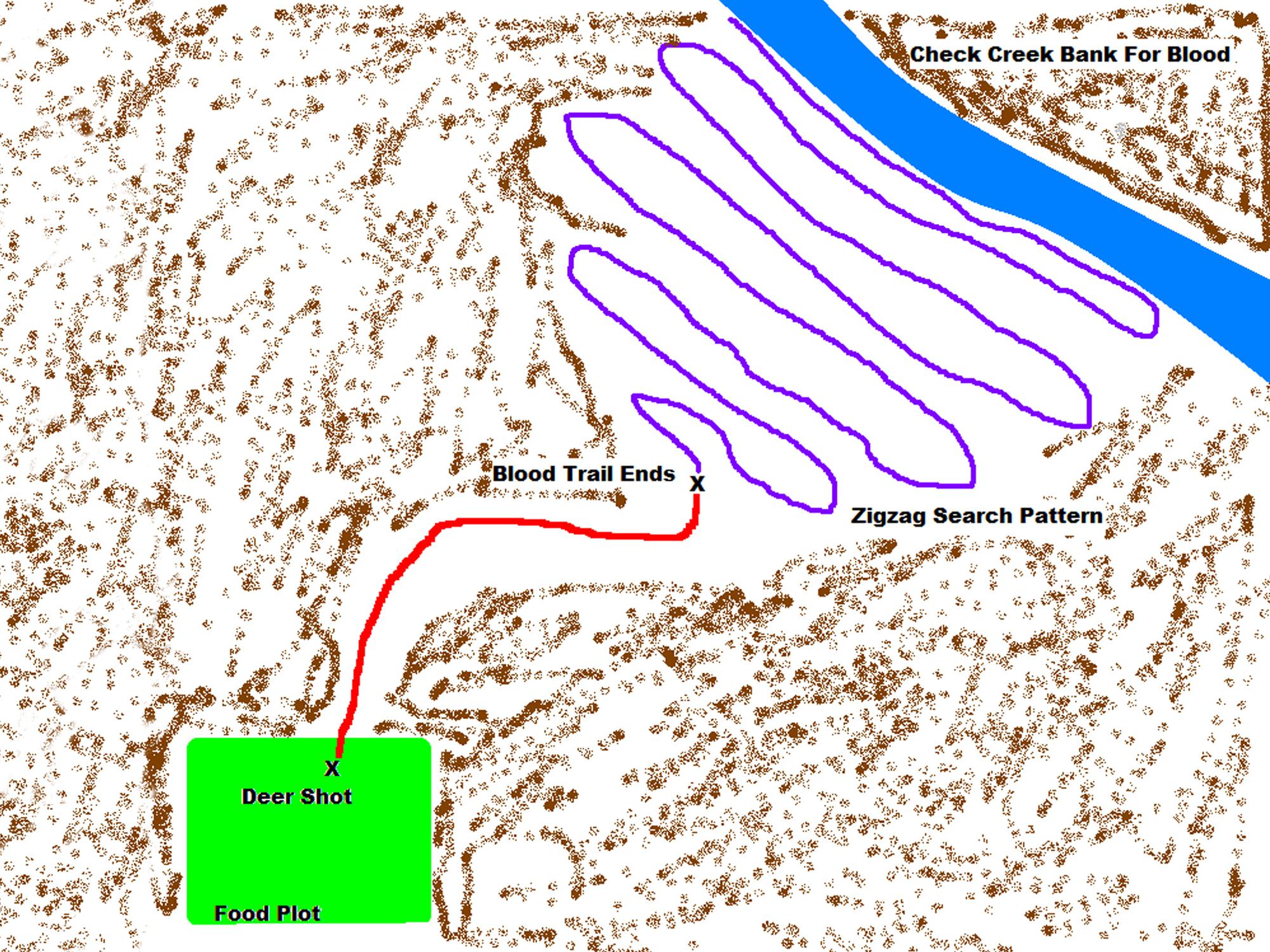

When the trailing begins, both Clay and Riley prefer to keep the number of trackers to a minimum. In most cases, their trailing teams consists of two members: a tracker and a spotter. The tracker actually does the blood trailing, while the spotter marks the last spot of blood found by the tracker. If the tracker loses the trail, he or she can go back to the spotter’s location and start searching for new sign all over again.

The only time a third person comes into the picture is when the blood trail completely plays out. At that point, the tracker and the third person can begin searching a zigzag pattern projecting outward from the last sign of blood and in the general direction the deer was headed.

If all else fails, the two guides suggest waiting until the next day and starting a grid pattern search of the area. You will want to call out the troops for this process. Using several trackers will make for a more thorough search. In a grid pattern search, trackers line up at 10- to 20-yard intervals at the site where the last blood was found. They then search for the downed animal by walking in lines parallel to one another and in the direction the deer was last headed. Any brush top, briar patch, ditch or thicket should receive additional scrutiny.

Since the vast majority of trailing is done at night, a good light is a necessity. However, you should consider other factors beyond brightness. There are the lights designed specifically for blood trailing. These lights use technology that filters reds and greens together to enhance the red color, making the blood trail much easier to follow.

Riley suggested getting lower to the ground when trailing at night, even if it means getting down on your hands and knees. From this angle, shine the light in the direction the deer is traveling to see blood that may not show up when you’re standing over it.

Both of the experts stress the importance of a positive attitude, even when things aren’t going very well. When you’re discouraged, it’s easier to overlook clues. Never give up on a blood trail if there is the slightest chance that the animal may be down.

Or as an old woodsman once said, “It’s not always the blood trail that will lead you to the deer, for it is so often the effort you put forth.”

Editor’s Note: Extension Outdoors is a column authored by several different experts in the Mississippi State University Extension Service.