Assessing and Protecting Water Quality in the Home and Community

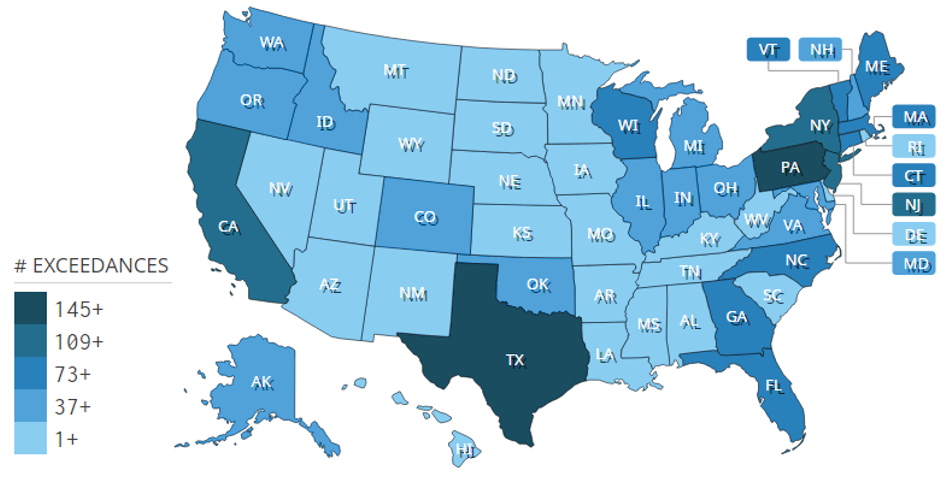

We may take for granted the clean water that pours from our household faucets, but clean water isn’t always a reality for people, even in some U.S. communities. USA Today (Young & Nichols, 2016) and The New York Times (Wines & Schwartz, 2016) report that excessive lead levels have occurred in over 2,000 water systems since 2012 (Figure 1). In Mississippi, elevated lead levels were detected in the Jackson area in July 2015.

The two major sources of contamination of home water supplies are aging water infrastructure (delivery pipes) and pollution of source drinking water. Poor water quality can negatively affect human and ecological health (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014; U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2015). Numerous natural and human-induced factors can affect water quality. Natural factors include geology, climate, vegetation, wildlife, and wildfires, and human-induced factors include point source pollution, non-point source pollution, and structural changes such as stream modifications.

Policies that Protect Water Resources

Appropriate water quality standards are determined based on the intended use of that water; drinking water standards are different from standards for water used to support aquatic life, for recreational use, or for irrigation. For example, water that contains suspended sediment particles may not be suitable for human consumption, but it would be perfectly fine for watering the lawn. Abundant water supplies may be of no use for agriculture production if the water is salty. Early detection of poor water quality and proactively guarding water resources are important actions to take to ensure that clean water is maintained in our homes and communities.

Currently, there are two major acts and a range of rules and regulations in place to help keep our waters safe. The Clean Water Act (CWA) of 1972 “establishes the basic structure for regulating discharges of pollutants into the waters of the U.S. and regulating quality standards for surface waters” (U.S. EPA, 2017a). The Safe Drinking Water Act of 1974 was established to protect the quality of drinking water in the United States. It “focuses on all the water actually or potentially designated for drinking use, whether from above (surface water) or underground (groundwater) sources” (U.S. EPA, 2017b).

The state of Mississippi is required under the CWA to establish, review, and update the state’s water quality standards. The current standards were adopted by the Mississippi Commission on Environmental Quality in 2016 (MDEQ, 2016). The CWA also gives authority to the state to designate uses for its surface waters. Degradation of designated waters is allowable under very limited circumstances, and anti-degradation policies protect water quality throughout the state.

Mississippi has established general conditions, which are minimum conditions applicable to all waters, and specific water quality criteria for different water use categories. These categories include: public water supply, shellfish harvesting, recreation, fish and wildlife, and ephemeral (temporary) waters. In the following sections, we will provide basic ways of identifying poor water quality and protecting clean water in your home and community.

Identifying Poor Water Quality at Home

Most Mississippians receive their water from one of two sources—public water works or private water wells. Many public water works use groundwater, in a similar way that private wells work. Private water wells are used often in Mississippi. In fact, 29 percent of people in our state’s most populated areas rely on a private well for their drinking water (Barrett, 2015). A few public water works rely on nearby surface waters, such as the Ross Barnett Reservoir near Jackson, to supply drinking water to their customers.

Whether your water comes from a public or private source, there are some basic indicators that your water is safe for consumption (Table 1). You should also note that, if your water comes from a public source, it will be treated and tested following federal and state regulations. Public water systems must notify the public of any violations of water quality standards, so it is not common to have a problem with water delivered from a public supply.

|

Concerns |

Common Signs |

Causes |

Recommended Tests |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Appearance |

Reddish-brown or yellowish |

Dissolved organic matter or iron |

Iron and tannin |

|

Appearance |

Frothy or foamy |

Detergents |

Detergents or total anionic surfactants |

|

Appearance |

Cloudy |

Suspended sediments |

Turbidity and total suspended solids |

|

Appearance |

Slimy, brown precipitate |

Dissolved iron with iron bacteria |

pH, iron, and bacteria |

|

Appearance |

Black flakes or particles |

Dissolved manganese |

pH and manganese |

|

Stains on bathroom fixtures or clothing |

Red or brown |

Dissolved iron |

pH and iron |

|

Stains on bathroom fixtures or clothing |

Yellow |

Dissolved iron, hydrogen sulfide, hard water |

pH, hardness, iron, and hydrogen sulfide |

|

Stains on bathroom fixtures or clothing |

Black |

Dissolved manganese, hydrogen sulfides |

pH, manganese, and hydrogen sulfide |

|

Stains on bathroom fixtures or clothing |

Green or blue |

Corrosive water, dissolved copper |

pH, hardness, alkalinity, saturation index, and copper |

|

Abnormal odor or taste |

Bitter |

Dissolved nitrate or sulfate |

Nitrate and sulfate |

|

Abnormal odor or taste |

Rotten egg |

Hydrogen sulfide |

Hydrogen sulfide |

|

Abnormal odor or taste |

Soapy |

Detergents, surfactants |

Detergents and total anionic surfactants |

|

Abnormal odor or taste |

Metallic |

Dissolved metals like iron, manganese, zinc, copper, lead |

pH, iron, manganese, zinc, copper, and lead |

|

Abnormal odor or taste |

Salty |

Excessive soluble salts |

Total dissolved solids, chloride, sodium, and electrical conductivity |

|

Abnormal odor or taste |

Septic, musty, earthy |

Decaying organic matter in the drain; pollution of well water from surface drainage; bacteria in the drain and/or well |

Bacteria and pH |

|

Abnormal odor or taste |

Gasoline, kerosene, oil |

Contamination by petroleum hydrocarbons, oil, and grease |

Petroleum hydrocarbons, oil, and grease |

|

Abnormal odor or taste |

Fruity |

Fuel spill, leaking underground fuel storage tank, road runoff, ponding near well |

Volatile organic compounds |

|

Other |

Corrosion of plumbing materials |

Corrosive water |

pH, hardness, alkalinity, saturation index, lead, copper, iron, manganese, sulfate, chloride, and electrical conductivity |

|

Other |

White deposits on bathroom fixtures and pots; soap scum |

Hard water |

pH, hardness, alkalinity, sulfate, and electrical conductivity (or total dissolved solids) |

|

Other |

Tarnished silverware |

Hydrogen sulfide gas |

pH and hydrogen sulfide |

|

Other |

Gastrointestinal illness (e.g., stomachache, nausea, diarrhea) |

Bacterial contamination, presence of excess nitrate, sulfate, and manganese |

Bacteria, nitrate, sulfate, manganese, and detergents |

|

Other |

Discoloration and/or mottling of children’s teeth |

Excessive fluoride |

Fluoride |

Adapted from Testing for Water Quality, Cooperative Extension, University of Georgia, Circular 858-2 and Water Quality Series: Drinking Water Testing, Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Service, AgCE-878.

Appearance

Perhaps the most obvious indicator of poor water quality is how it looks. If water from the faucet appears cloudy or foamy, has particles floating in it, or has a reddish-brown or yellow color, it is best to assume the water is not safe for drinking until further tests are conducted. Commonly, reddish-brown or yellowish water is associated with iron and tannins from iron pipes or dissolved organic matter (tree leaves that have decomposed into microscopic particles) entering your home water system. Sometimes sediment can get into your water from a broken water line, in which case a boil water notice will be in place.

Sometimes poor water quality becomes apparent on bathroom fixtures or clothes. Staining or deposits that are red or brown, yellow, black, and green or blue can indicate numerous problems, from hard water (dissolved carbonate) to dissolved metals or algae. Most of the minerals found in drinking water are at safe, sometimes beneficial, levels for human health. However, frequent, high concentrations of these minerals can have harmful effects. For example, “low levels of [lead] exposure have been linked to damage to the central and peripheral nervous system, learning disabilities, shorter stature, impaired hearing, and impaired formation and function of blood cells [in children]” (U.S. EPA, 2016).

Odor and Taste

If your water smells or tastes bad or unusual, you should use caution before drinking or cooking with it. Sometimes odors come from sink drains and not necessarily the water. Pour water from the faucet into a glass and move away from the sink to determine if the water is the source of the smell.

Common odor problems are from water treatment, bacterial growth, or organic matter decay. Often these smells or tastes aren’t a problem, such as a bleach taste from a chlorination shock to prevent bacterial contamination of the water system. Actually, typical levels of chlorine in drinking water from public water works range from 0.2 to 5.0 ppm (Saha et al., 2012), while the optimal range for a chlorine residual is specific to the public water system, typically falling between 0.1 to 1.0 ppm. The U.S. EPA maximum contaminant level goal for chlorine is 4 ppm (2017c). Exposure to air for a few minutes will help dissipate the chlorine and the odor.

Fuel-like odors are a more serious problem and can result from leaking fuel tanks, discharge from industry or landfills, or oil and hydrocarbons from road and parking lot run-off. These types of odors or tastes should be reported to the county health department, as there is increased risk of health problems from inhaling or consuming fuel/gas.

Resources and Support

You may not always be able to recognize poor water quality from appearance, odor, or taste. Some contaminants are not noticeable but can still affect human health. For this reason, everyone should contact the managing board of their local public water system for information regarding their water quality. You can find contact information or reports by searching the keywords “EPA Consumer Confidence Reports” and using the “Find your local CCR” tool on the EPA’s website.

If you are one of the many Mississippians who use a private well, you should test for nitrates and bacteria at least once a year. Contact the testing laboratory you plan to use, and ask about sampling, handling, and shipping procedures (if necessary) to ensure that your test results are accurate. It is a good idea to have your water tested in multiple seasons throughout the year.

Your physician may also request a water quality test if the health of family members, pets, or livestock changes. For more information about private well testing, please see Mississippi State University Extension Publication 1872 Protecting Your Private Well (http://extension.msstate.edu/publications/publications/protecting-your-private-well).

Protecting Water Quality at Home

You can protect your water at home by monitoring its condition using the basic methods outlined above. Have bacteriological and basic water chemistry tests conducted annually for private wells, or view the annual reports from the local public water system (Table 2). You should also monitor for sources of contamination on your property (e.g., chemical or fertilizer spills), especially if you have a private well. It is good to check for burst pipes (stemming from aging infrastructure), which can lead to loss of water pressure, water damage to buildings and appliances, and sewage or chemical leaks.

If you do notice potential contamination on your property, contact the Mississippi Department of Environmental Quality. Their spill response teams can help minimize the impacts to water, the environment, and human health. If you notice degrading or damaged infrastructure, have it replaced as soon as possible, then follow through with water quality testing to ensure safe drinking water. Personnel at the Mississippi State Department of Health can help you with water quality problems in your home or public buildings. See Table 3 for select EPA standards governing drinking water quality.

Table 2. Generally recommended water tests for private wells.

Minimum Testing Recommendations

|

Testing Objective |

Type of Test |

Testing Frequency |

|---|---|---|

|

Well maintenance |

Bacteria |

Annual |

|

Well maintenance |

Nitrates (total nitrate and nitrate + nitrite) |

Annual |

|

Well maintenance |

Turbidity and color |

Annual |

|

Well maintenance |

Comprehensive water chemistry: basic water chemistry (see below) plus alkalinity, soluble salts (or total dissolved solids), nitrate, chloride, fluoride, and sulfate |

Initially and then every 3 years |

|

Well maintenance |

Basic water chemistry: pH, hardness, aluminum calcium, chromium, copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, and zinc |

Annually after initial comprehensive water chemistry |

Additional Testing Recommendations

|

Testing Objective |

Type of Test |

Testing Frequency |

|---|---|---|

|

Verification of potential contamination |

Lead and copper |

At least once and then yearly follow-up for: 1) houses with plumbing that predates the 1987 plumbing codes with copper piping with lead solders 2) very old houses in which there are lead pipes 3) houses with brass and/or chrome fixtures (brass contains 3–8% lead; chrome fixtures contain lead) |

|

Verification of potential contamination |

Arsenic |

At least once and then a yearly follow-up |

|

Verification of potential contamination |

Uranium |

At least once and then a yearly follow-up |

|

Verification of potential contamination |

Volatile and semi-volatile organic compounds, pesticides, petroleum hydrocarbons, and other organics |

Not required on a regular interval; recommended only when contamination is suspected. |

Adapted from Testing for Water Quality, Cooperative Extension, University of Georgia, Circular 858-2 and Water Quality Series: Drinking Water Testing, Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Service, AgCE-878.

Table 3. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency drinking water standards for select contaminants.

Primary contaminants

|

Contaminant |

Maximum Concentration Limit |

|---|---|

|

Arsenic |

10 ppb |

|

Lead |

15 ppb |

|

Total coliform |

0 MPN/100 mL |

|

E. coli |

0 MPN/100 mL |

Secondary contaminants

|

Contaminant |

Maximum Concentration Limit |

|---|---|

|

Aluminum |

0.2 ppm |

|

Iron |

0.3 ppm |

|

Manganese |

0.05 ppm |

|

Sulfate |

250 ppm |

Adapted from Testing for Water Quality, Cooperative Extension, University of Georgia, Circular 858-2 and Water Quality Series: Drinking Water Testing, Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Service, AgCE-878.

Protecting Water Quality in Your Community

Recognizing poor water quality in lakes, rivers, streams, and ponds is important for our recreational uses of these water bodies, for the wildlife that depend on them, and for aquatic plants and animals that live in them. Protecting water quality in these aquatic systems is just as important as protecting water quality at home. Mississippi’s recreational opportunities, including hunting, fishing, hiking, camping, birding, and boating, are very important to the state’s economy (Baker, 2016).

The basic principles of monitoring water quality in your community and in your home are similar. However, the appearance and odor of outdoor water resources is more variable because of temperature fluctuations, rain, and biological factors. Appearance and odor of community water resources become a concern when they are abnormal for extended periods of time. Sustained chemical or sewage-like odors are indicators that community water resources should be tested for contaminants. Unmanaged water quality problems can lead to health issues for wildlife and people.

What You Can Do

Citizens can help protect water quality by monitoring the appearance and odor of community water sources. One of the best and simplest ways to be more involved is to become aware of water bodies near you; online mapping services can be helpful in identifying these.

Get to know local ordinances and state laws that protect your local surface waters from harmful pollution. Become a part of the public water quality discussion. Contact the managing board of your local public water system or the mayor’s office to learn about measures to protect local water sources. Be sure to attend public meetings regarding water concerns, issues, proposals, protections, and ordinances.

You might also want to start, support, or join a local Adopt-A-Stream program, Waterkeeper Alliance group, Water Watch group, or EarthEcho Water Challenge program. Through these groups, you can conduct basic water chemical and bacteriological monitoring efforts and contribute to scientific databases. In addition, you can become a member of nonprofit organizations geared toward protecting environmental and/or drinking water, such as American Rivers, Ducks Unlimited, 1 Mississippi, Mississippi Wildlife Federation, or the Nature Conservancy of Mississippi (see Table 4).

If we all take an active role in protecting our water resources today, we can help preserve these resources for future generations.

|

Agency |

Office or Program |

Contact Website |

|---|---|---|

|

Mississippi Department of Environmental Quality |

Water Quality Assessments |

https://www.mdeq.ms.gov/water/field-services/water-quality-assessment/ |

|

Mississippi Department of Environmental Quality |

Water Quality Standards |

https://www.mdeq.ms.gov/water/surface-water/watershed-management/water-quality-standards/ |

|

Mississippi State Department of Health |

Bureau of Public Water Supply |

|

|

American Rivers |

Southeast Region |

|

|

Ducks Unlimited |

Mississippi Chapter |

http://www.ducks.org/conservation/how-du-conserves-wetlands-and-waterfowl |

|

The Nature Conservancy |

Mississippi Division |

https://www.nature.org/en-us/about-us/where-we-work/united-states/mississippi/ |

|

Mississippi Wildlife Federation |

Adopt-A-Stream Mississippi |

|

|

1 Mississippi |

River Citizen Program |

|

|

Waterkeeper Alliance |

no Mississippi chapters |

|

|

Global Water Watch |

no Mississippi chapters |

|

|

EarthEcho International |

Water Challenge Program |

http://www.worldwatermonitoringday.org/about |

References

Baker, B. H. (2016). Don’t overlook the value of outdoor recreation. Starkville Daily News, Starkville, MS.

Barrett, J. (2015). Mississippi private well populations. Mississippi State University Extension Service: Publication 2775. http://extension.msstate.edu/publications/publications/mississippi-private-well-populations

Barrett, J. (2015). Protecting your private well. Mississippi State University Extension Service: Publication 1872. http://extension.msstate.edu/publications/publications/protecting-your-private-well

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Water-related diseases and contaminants in public water systems. https://www.cdc.gov/healthywater/drinking/public/water_diseases.html

Kelly, J., & Nichols, M. (2016). How USA TODAY ID’d water with high lead levels. http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2016/03/16/how-water-systems-identified/81281114/. Image Source: USA TODAY analysis of EPA’s Safe Drinking Water Information System (SDWIS) database.

Mississippi Department of Environmental Quality. (2016). Water quality standards. https://www.mdeq.ms.gov/water/surface-water/watershed-management/water-quality-standards/. Note: There are multiple links on this webpage to water quality information in Mississippi.

Saha, U., Sonon, L., Mowrer, J., & Kissel, D. (2012). Your household water quality: Odors in your water. Cooperative Extension, University of Georgia Circular 1016.

Saha, U., Sonon, L., Turner, P., Mowrer, J., & Kissel, D. (2013). Testing for water quality. Cooperative Extension, University of Georgia Circular 858-2. Note: Original manuscript written by Atiles, J., & Vendrell, P.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2016). Basic information about lead in drinking water. https://www.epa.gov/ground-water-and-drinking-water/basic-information-about-lead-drinking-water

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2017a). Summary of the Clean Water Act. https://www.epa.gov/laws-regulations/summary-clean-water-act

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2017b). Summary of the Safe Drinking Water Act. https://www.epa.gov/laws-regulations/summary-safe-drinking-water-act

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2017c). National primary drinking water regulations. https://www.epa.gov/ground-water-and-drinking-water/national-primary-drinking-water-regulations#one

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. (2015). Water quality. https://www.fws.gov/ecological-services/habitat-conservation/water-quality.html

Wines, M., & Schwartz, J. (2016). Unsafe lead levels in tap water not limited to Flint. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/09/us/regulatory-gaps-leave-unsafe-lead-levels-in-water-nationwide.html?_r=0

Young, A., & Nichols, M. (2016). Beyond Flint: Excessive lead levels found in almost 2,000 water systems across all 50 states. http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/2016/03/11/nearly-2000-water-systems-fail-lead-tests/81220466/

Publication 3242 (POD-05-21)

By Beth Baker, PhD, Assistant Extension Professor; Caleb Aldridge, Graduate Research Assistant, and Austin Omer, PhD, former Extension Associate, Wildlife, Fisheries, and Aquaculture.

The Mississippi State University Extension Service is working to ensure all web content is accessible to all users. If you need assistance accessing any of our content, please email the webteam or call 662-325-2262.