Economic and Community Programming in Mississippi

Introduction

As one of the base programming areas of Extension, economic and community development (ECD) touches a wide array of stakeholders residing and/or working in Mississippi communities. Through educational programs and technical assistance activities, Extension faculty in the Mississippi State University Department of Agricultural Economics work with individuals, businesses, civic and professional groups, elected and non-elected community officials, and other stakeholders to address issues in both rural and urban communities across the state. The goal of this publication is to provide a history of this area of Extension programming, discuss the reasons for its continued importance, and highlight several programming activities that these faculty provide to clients.

History of the Cooperative Extension Service

Cooperative Extension was established in 1914 with the passage of the Smith-Lever Act. But Extension has roots that long precede the passage of this historic piece of legislation. Agriculture clubs and societies began in this country in the late 1700s. The farming journal American Farmer encouraged farmers to share their achievements and methods of solving problems beginning in the early 19th century.

While the Smith-Lever Act charged Cooperative Extension with a mission of “diffusing among the people of the United States useful and practical information on subjects related to agriculture, home economics, and rural energy,” the Bankhead-Jones Act expanded the mission amid the Great Depression. The Act’s phrase “the development and improvement of the rural home and rural life, and the maximum contribution of agriculture to the welfare of the consumer and the maintenance of maximum employment and national prosperity” formalized the rationale that the unique concept of cooperative extension should expand beyond the farm and the home to work with the communities where workers are employed and residents live.

After the Bankhead-Jones Act was passed, this area of cooperative extension has undergone many name changes and programming directions, but the basis of this work has remained constant with extension’s mission outlined in the Smith-Lever Act. It has been suggested that the function of extension is as follows:

- Diffusion of information

- Development of interest in and recognition of significant problems

- Encouragement of planning the best ways and means of solving the problems recognized

- Stimulation of appropriate action by the people themselves by the decisions they have reached

These functions, particularly considering extension’s three-fold funding mechanism (federal, state, and local funding), provide effective insight on how community resource development programming should be implemented.

Community Resource Development Focus

One of the most striking explanations of the need for extension and the community resource development programming area can be found in President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s Special Message to Congress concerning a program for low-income farmers. In this message, Eisenhower stated:

In the wealthiest nations where per capita income is the highest in the world, more than one-fourth of the families who live on American farms still have incomes of less than $1,000 [approximately $11,172 in 2023 dollars]. They neither share fully in our economic and social progress nor contribute as much as they would like and can contribute to the Nation’s production of goods and services.

Curtailed opportunity begets an economic and social chain reaction which creates unjustified disparity in individual reward. Participation diminishes in community, religious, and civic affairs. Enterprise and hope give way to inertia and apathy. Through this process, all of us suffer.

These words, as true today as in 1955, provide a comprehensive expression of the need for cooperative extension’s community-related programming efforts to continue. Evidence has shown that the rural-urban wage gap is rising, the civil activities and engagement of people are falling, and the labor force is declining in population and capacity.

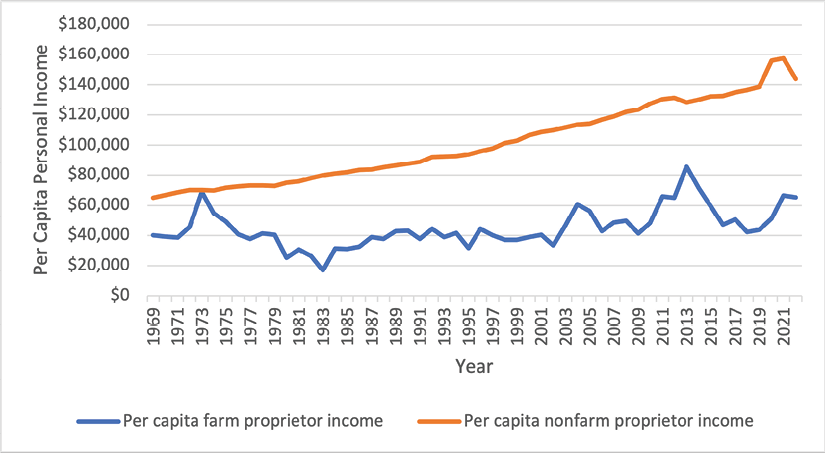

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis and the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank, presented in 2023 dollars.

While data from 1955 is not readily available, Figure 1 demonstrates the gap between real (adjusted for inflation) per capita farm proprietor income and real per capita nonfarm personal income for the U.S. As shown in the graphic, the gap between these metrics widened over the 1969 to 2022 period. The year 1973 is the only time when the two metrics were close to being equal, mainly due to increased levels of farm income resulting from very large increases in grain exports to the Soviet Union. This led to dramatic, albeit short-lived, increases in agricultural commodity prices and the “hamburger boom” that resulted from increased marketing efforts by fast food restaurants.

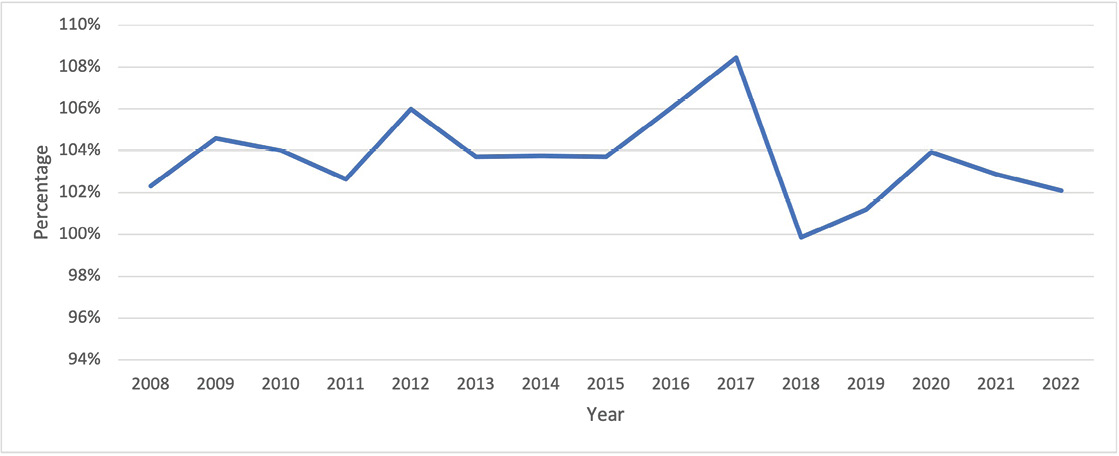

Figure 2 presents the metro-to-nonmetro per capita income gap for Mississippi with adjustments made for the estimated differences in the cost of living between metropolitan and nonmetropolitan areas. Income (which includes salaries and wages, transfer payments, government social insurance contributions, adjustment for residence, dividends, interest, and rent) is likely a more meaningful metric than the wage gap. This figure shows a different situation for Mississippi than for most other states; namely that nonmetro incomes are higher than metro incomes in the state when adjusted for parity between prices. This is mainly due to the cost of housing in metro areas versus nonmetro areas. For goods, utilities, and “other” categories, the average percentage difference between metro and nonmetro area price parities (a measure of the relative prices of goods and services purchased by households) is 1.5 percent for 2008–2022. However, the average percentage difference in price parities for housing between 2008 and 2022 is 45.1 percent; in other words, the cost of housing in Mississippi nonmetro areas is less than half of the cost in metro areas.

While this change is erratic over time, there is only one year (2018) where nonmetro incomes are lower than metro incomes when adjusted for parities (this was due to a relatively sharp decrease not only in the price parity measure for metro housing but also a drop in the price parity measures for metro goods and metro utilities. This situation is likely present in Mississippi because the Mississippi population is fairly evenly split between metro and nonmetro areas (the 2022 Mississippi nonmetro population was 51 percent of the total population). This is not the case in most other states. For example, the 2022 Alabama nonmetro population was 23.4 percent of the total population, and the 2022 Tennessee nonmetro population was 21.6 percent of the total population. These statistics infer both unique challenges and opportunities for ECD Extension programming in Mississippi.

The scope of extension programming in this area has changed over the years. The Smith-Lever Act specifically mentioned the area of rural energy; this legislation was passed as widespread electrification was taking place in the country’s more urban areas, and the legislation’s authors likely saw the benefits of this energy source for agriculture.

The Rural Development Program Handbook was developed by the chairs of 31 state rural development committees to outline a comprehensive effort that would address the issues in President Eisenhower’s letter to Congress. It is important to note that while this rural development program was not explicitly a Cooperative Extension program, Cooperative Extension administrators chaired 29 of the 31 state rural development committees that contributed to the report.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis: Real per capita personal income by portion and regional price parities by portion.

The handbook identified three objectives that closely aligned with President Eisenhower’s letter. These objectives are:

- To expand industry in underdeveloped rural areas and widen the range of off-farm job opportunities

- To help families that have the desire and ability to stay in farming gain the necessary tools, land, and skills

- To help people in underdeveloped rural areas enjoy better opportunities for adequate education, vocational training, and improved health

In 1975, the National Association of State Universities and Land-Grant Colleges (now known as the Association of Public and Land-grant Universities or APLU) commissioned a task force to provide a report to the Extension Committee on Organization and Policy (ECOP). Titled “Community Development: Concepts, Curriculum, Training Needs,” this document expanded the national view of community resource development programming.

The association’s task force report identified eight areas of community development on which Cooperative Extension educational programming should focus. These included:

- community development as a concept

- learning concepts

- sociological concepts

- geographic concepts

- political concepts

- economic concepts

- feasibility concepts

- property rights concepts

In addition to the above focus areas, the report outlined several concepts that the task force deemed essential. A brief overview of these concepts includes:

- Community – one or more groups of people interrelating for the attainment of goals in which they share a common concern

- Development – the process of progressive change in attaining individual and community goals

- Community development process – an open system of decision-making whereby those comprising the community use democratic and rational means to arrive at group decisions and to take action to enhance the social and economic well-being of the community

The latest “evolution” in community development Extension programming from a national perspective came from the Denver Team, a group that met in Denver, Colorado, in 2004 to formulate a systematic method to address the underlying tenets of Extension programming in community development. This team developed the basic foundations for implementing community development Extension programming across the nation and, by Extension, in Mississippi. This foundation is divided into three basic components, with specific subject areas in each component.

- Understanding communities and their dynamics

- basic understanding of community

- community situational analysis

- community power structure

- community economics

- community demographics

- social action process

- Developing successful community initiatives

- principles of community development practice

- ensuring broad-based participation and bringing people to the table

- participatory planning

- implementation and project planning

- facilitating group meetings

- building community collaborations

- evaluation and feedback

- Areas of specialization and emphasis

- economic development diversity and vitality

- local government

- natural resources

- group process and facilitation

- organizational development (including nonprofits and volunteerism)

- leadership and civic engagement

- public issues education

- community services

- workforce development

Around the United States

An examination of the Extension Service websites and the land-grant institutions’ programs of 1862, 1890, and 19941 revealed several organizations that have community and/or economic development programming refer to this programming by various names (see the Appendix for a list of the institutions reviewed and the websites, if available, for these types of Extension programs). This examination revealed that these programs are branded in several different ways including, but not limited to:

- community development

- communities for a lifetime

- community vitality

- business and community

- economic development

- leadership and civic engagement

- land stewardship

- community resource development

The branding of the program area by a particular Extension service or program tends to highlight the major efforts of the institution in the area. For example, while a program branded as leadership and civic engagement may well offer economic analyses as part of its efforts, it appears, at least from the website analysis, that major emphasis is placed on engagement-type programming activities. Furthermore, it seems plausible that various units or sections within an Extension service or program would refer to individual ECD efforts by labels different than the overall program effort. For example, the Mississippi State University Extension Service refers to this program area as community on its website, but specialists within the Department of Agricultural Economics tend to refer to it as economic and community development since economic analysis is where most of those specialists’ efforts lie.

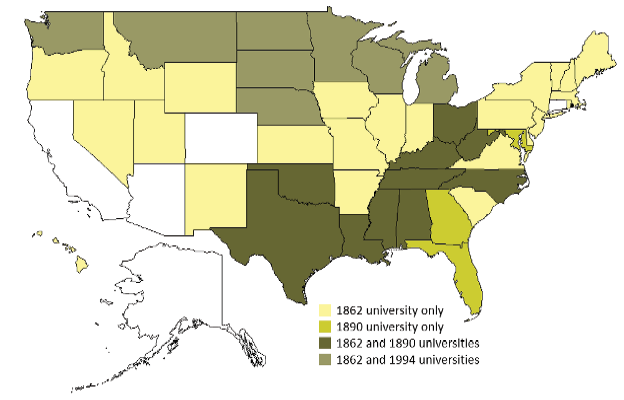

The website examination revealed that all but five states (Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, and Connecticut) have at least one Extension service or program that offers economic and/or community development programming for residents2. Figure 1 provides information on the numbers and types of Extension services/programs from 1862, 1890, and 1994 institutions that offer these types of programs. Twenty-four states only offer these programs through an 1862 land-grant institution (many of these states, particularly in the Northeast, do not have an 1890 or 1994 institution). Florida, Georgia, and Maryland only offer these types of Extension programs through their 1890 institutions. Nine states had this type of programming offered through both 1862 and 1890 land-grant institutions, and eight states had this programming offered through both 1862 and 1994 institutions (see Figure 3 on page 5).

It is important to note that even if a particular Extension service or program did not appear to have a programming emphasis in this area, it does not mean that the institution is not accomplishing valuable work in this area. It simply means that these programs cannot be readily identified by examining the institution’s website. For example, the Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (IFAS) Extension at the University of Florida reports substantial impacts in the community resource development arena, but no link describing the program can be found. Likewise, faculty in the University of Georgia’s College of Family and Consumer Sciences are focusing on the community development area, but resources describing the community development programming area could not be found.

In addition, there are many institutions that engage in this type of work but are not typically considered to be land-grant universities. The University of California Irvine School of Law sponsors the Community & Economic Development Clinic to focus on issues of community and economic development in low- and moderate-income populations.

Economic and Community Development Extension Programming in Mississippi

The ECD programming area within MSU Extension is the broadest of the four base programming areas, which include agriculture and natural resources (ANR), family and consumer sciences (FCS), and 4-H youth development (4-H), as well as ECD.

ECD programming in Mississippi touches virtually all Mississippians’ lives through various direct and indirect efforts. From providing current economic information to elected officials and public policymakers to educational programming designed to help low-income families manage their income and expenses, ECD has various educational resources designed to help Extension professionals address community problems and issues.

To develop an effective ECD Extension educational program at the community level, it’s important to define the program area. Some in Extension have defined ECD as anything that does not fall into the ANR, FCS, or 4-H programming areas. However, this type of logic leads to a mixed set of activities that does not encompass or contribute to an educational program.

ECD faculty in agricultural economics at MSU have developed the following definition:

Economic and community development is a process by which community members collaborate to make group decisions and take actions to enhance the community’s economic and/or social well-being.

The process focuses primarily on assisting communication in the decision-making process through effective facilitation and intensive subject matter analysis, as well as providing educational and technical assistance resources to help the community implement programs focusing on the economic and institutional components identified in the decision-making process.

While the decision process will change depending on the issue being addressed, several factors should likely be considered regardless of the issue. These include an analysis of the change forces that are present within the community, shifts in the types of employment and business/industry structure that have occurred over time, the role that local government plays in addressing the issue, and the role of existing economic and social organizations as well as the emergence of new organizations that affect the issue.

The preceding definition of ECD Extension programming has its foundation in the following definitions of its components:

Development

Development is a common term that can mean many things to different people. In this context, however, the term has a very specific meaning. In our ECD Extension programming efforts, development is a process through which community (and hopefully) individual interests, wants, and needs can be attained through an expanded, intensified, or adjusted use of available resources. Sustainable or long-lasting development typically includes identifying community and individual interests and pursuing resources that allow the objectives to be realized and the goals achieved.

The goal of “development” in this context is to improve the quality of life for the community’s members or residents. In other words, development should be a process of improvement.

Economic

As was previously mentioned, many facets to a community can be “developed” to improve the quality of life for its members. These include working with a community to enhance civic engagement for a more responsive government, developing a pre-K educational program for children, and many others. This implies that there are many facets of the geographic “place” that we refer to as community where the Extension professional can devise educational programming to facilitate or form collaborations that enhance the opportunities for residents to have access to higher incomes, an increased number of jobs, and a better overall quality of life.

Economic educational programs that help stakeholders achieve the above objectives can take many forms. Subject matter specialists in Mississippi provide several products that stakeholders can use to gauge the state of their local economy. A partial listing of these products include:

Economic Environment

- A series of eight municipal and county profiles that describe the state of various economic sectors.

- Extension faculty perform numerous economic impact/contribution studies focused on economic activities occurring within a community. These studies include topics such as the economic impact of the opening (or closing) of a major tourism venue, the economic impact of the emergence of an industry or business in the community, the economic impact of spending by visitors to a local crafts festival or rodeo, or the economic impact that a potential grocery store or other retail establishment would have on the local or regional economy.

- Extension faculty also perform specialized analyses of an individual community’s ability to support a specific type of business. Past analyses have included the ability of the community to support additional apartment-type housing in an area that is experiencing significant economic growth or a grocery store in an area that has typically been considered a food desert.

Business Assistance and Planning

- Extension faculty have presented educational programs focused on helping potential small business owners improve their personal financial wellness and readiness to become better equipped to start a small business.

- The Bricks-to-Clicks Marketing Program provides practical and effective instruction to business and nonprofit managers in the use of social media marketing strategies.

- Extension faculty have participated in and/or led several interdisciplinary teams to assist potential entrepreneurs in determining the feasibility of value-added enterprises (both agricultural and non-agricultural enterprises). Specific studies have addressed such potential operations as custom livestock slaughter facilities and tourism enterprises that may evolve as part of a disaster recovery effort.

- Extension faculty in agricultural economics have collaborated with faculty at other universities to develop and teach economic development strategies designed to identify factors critical to retaining and expanding existing businesses in the local community. These programs are local, place-based efforts that can provide tremendous insight into the issues faced by businesses that are an integral part of the community’s social fabric.

- Extension faculty work with public utilities in developing financial management plans, cost analyses, and utility rate decision tools. These studies provide government entities and non-profit corporations with the information needed to determine the true cost of public services (water, wastewater, natural gas, and garbage pickup) so that equitable and efficient rates can be developed to cover the current costs and future capital expenditures necessary to maintain the utility for future service and environmental sustainability.

Community

The definition of community is one of the most difficult concepts to understand that we deal with concerning Extension programming. Working with a community means working with people with a similar set of interests and/or goals. It is generally accepted that to affect real and sustainable change, the community must be place-based; that is, it will likely encompass some specific geographic area. However, this area should not be limited to “artificial” boundaries such as city or county borders. In many cases, the community may be an area comprising parts of several cities or counties without containing the whole. It should be realized that the geographic area and the people who define the community may vary greatly depending on the type of problem or issues being addressed.

In addition to the economic programs outlined above, MSU Extension works with community leaders (both elected and non-elected) and other stakeholders to address issues that may be either conducive or detrimental to a sense of community in specific places. These programs include the following:

- Extension personnel work with local communities to develop and implement local, place-based community planning activities designed to address such issues as race, poverty, and economic development that can have a significant impact on the community’s sense of inclusion and ability to attract new (and retain existing) residents.

- Extension faculty provide socio-economic data to community and non-profit leaders to use in securing funds for community-oriented projects such as cultural museums/centers, community centers, and upgrades to existing community buildings.

- Extension personnel collaborate with community stakeholders and external parties (government agencies, philanthropic organizations, etc.) to address specific issues or initiatives that are critical to the presence of community. These collaborations can address issues such as disaster recovery, racial reconciliation, poverty, or broadband internet accessibility throughout the state.

In the Department of Agricultural Economics, Extension faculty focus on a variety of needs for our clients in the state. Specific areas addressed include, but are not limited to:

- the Extension Center for Economic Education and Financial Literacy

- assisting the Office of Broadband Expansion and Accessibility of Mississippi in developing a 5-year plan for broadband expansion and access

- public utility rate analysis and financial management

- the Bricks-to-Clicks Marketing Program for businesses, non-profits, and tourism organizations

- economic impact and contribution analysis to determine the economic spillover effects of industries and sectors within a specific region

- economic profiles describing the state of a specific region’s economy. Standard profiles are focused on the economics of retail trade, poverty status, the health sector’s economic contribution and status, the economic contribution of agriculture, and the general economy’s economic status. Geographic areas include the state, counties, towns/cities, congressional districts, and Extension regions.

- focused economic analyses of specific regions and business sectors

- business retention and expansion visitation programs

- entrepreneurship and small business development

- community strategic planning

Delivery of Economic and Community Development Programming

There are many strategies that can be effective in delivering ECD subject matter to community-based stakeholders. One of the most used methods is the direct delivery of the material or analysis by the subject matter specialist to the stakeholder or end user (including the development and use of interdisciplinary teams). This is usually the method that is used in Mississippi by agricultural economics faculty due to the technical nature of the subject matter and the lack of educational opportunities to train county- and area-based faculty and professional staff. While this method has proven to be relatively effective, it is likely not as efficient as it could be. This inefficiency may be remedied by specialists offering an increased number of educational opportunities to county- and area-based faculty and professional staff to equip them to deliver these types of materials; that is, to more fully develop the so-called “train the trainer” models.

Another method that is often used in the economic and community development area involves the subject matter specialist equipping the county- and area-based faculty and professional staff to deliver content to end-user stakeholders. Program areas where this has been successful are typically more closely aligned with the traditional Extension education program planning model and have included activities such as community strategic planning and its components (i.e., community listening sessions), identification of areas of need for community-oriented services and activities, identification and development of new community facilities or upgrades of existing facilities, and identification of activities and programs that contribute to the development of a sense of community among area residents; again, this could be delivered by area and county Extension professionals through a “train the trainer” model.

Finally, ECD faculty in agricultural economics have delivered synchronous and asynchronous online training (including podcasts) in the areas of Vibrant Communities, Local Flavor (local foods), and Bricks to Clicks.

Program Identification, Development, Implementation, and Evaluation

Unlike states such as Minnesota and Wisconsin, the development and delivery of educational programs in Mississippi in the ECD area tends to be different from the development and delivery of programs in the agriculture and natural resources and family and consumer sciences areas. These program areas have subject-matter-trained county and regional agents and specialists who often take an active role in planning, developing, and implementing programs in those areas.

In Mississippi, the ECD programs are primarily identified, developed, and delivered by state specialists. But the program planning and development process is basically the same. First, a client need is identified. There are several methods that can be used to identify the need. The New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station’s webpage, Conducting Needs Assessments, provides information on several methods of conducting needs assessments that can be used in determining the needs of stakeholders. In particular, the “Needs Assessment Primer” defines a “need” as the gap between what is and what should be or what is desired to be.

Two current Mississippi ECD programs specifically use this gap to articulate the needs of stakeholders. First, the Bricks-to-Clicks program considers the gap between the current level of business profits and the desired level of these profits. Second, the economic development program recognized that there was a gap in the information that community leaders possessed and the information that they needed to possess to make informed decisions regarding the strategies that could be adopted to increase jobs, incomes, and the quality of life in their communities.

Once the need is identified, adequate research must be undertaken to determine the strategies or methods that would be effective in bridging the needs gap. In the case of the Bricks-to-Clicks program, it was determined that effective use of social media platforms as marketing tools would bridge this gap for small- and medium-size business owners. For the economic development program, Extension specialists worked with stakeholders to determine the information that was needed for those stakeholders to make better informed decisions. For this program, a number of strategies was envisioned, including economic profiles for the municipalities, counties, and regions of the state, appropriate methods to analyze issues, and educational materials to explain the concepts addressed by faculty members in the department.

As previously mentioned, these materials and analyses have primarily been delivered by specialists and other faculty, mainly due to the technical nature of the analyses. However, there are multiple opportunities for county and regional educators to become involved in the process. The majority of the economic profiles have accompanying PDF presentations that can be used by county educators to present the material to audiences. In many cases, specific analyses, particularly economic impact and contribution analyses, have been provided to county faculty, and those faculty have explained the results of those analyses to local stakeholders and community leaders. Furthermore, these publications showcase the work of Extension by providing research-based evidence of its educational programming impact.

An ideal situation would be for county/regional educators to work closely with the analyst to examine the issue, assist in developing the analysis, and present the results to local leaders and stakeholders. This approach has many benefits for the local community.

Conclusion

Extension programming in economic and community development is a vital and vibrant component of Mississippi State University Extension. Faculty members in Agricultural Economics, as well as other units within the Mississippi State University Extension Service and the Extension programs at Alcorn State University, maintain a variety of programs designed to assist Extension professionals, elected officials, community and business leaders, and residents to develop and achieve a vision for their community. For more information, please contact one of the following faculty members or your local county Extension office.

Alan Barefield

662.325.7995

James Barnes

662.325.1796

Devon Mills

662.686.3215

Becky Smith

662.325.1793

References

Ayers, J., Barefield,A., Beaulieu, B., Clark, D., Daniels, S., French, C., Howe, R., Leuci, M., and Senese, D. (2005). Foundations of practice: Cooperative Extension’s community development foundation of practice.

Barnes, J. (2020). Bricks-to-clicks online marketing and education for businesses. Mississippi State University Extension. Publication P3150.

Barnes, J. (2023). Unveiling a new online marketing program for extension programs: The seven fundamental elements. Journal of the NCAA. ISSN 2158-9459. Volume 16, Issue 1.

Bottum, J.S., Phifer, B.M., Boyle, P.G., Brown, E.J., Clegg, D.O., Dolan, R.J., Neely, W.V., Sorensen, D.M., and Vlasin, R.D. (1975). Community development: Concepts, curriculum, training needs – A task force report to the extension committee on organization and policy. National Association of State Universities and Land-Grant Colleges.

Committee for Rural Development Program. (1959). Rural Development Program Handbook.

Eisenhower, D. D. (1955). Development of Agriculture’s Human Resources. Letter of Transmittal.

National Education Association. (2022). Land grant institutions: An overview. NEA Research Land Grant University Brief, No. 1. 2022.

Rao, S.S. (1960). Role of extension service in rural development. Problem in lieu of thesis. University of Tennessee.

United States Congress. Smith-Lever Act. ch. 79, 38 Stat. 372, 7 U.S.C. 341. May 8, 1914.

United States Congress. Land Grant & Sea Grant: Bankhead-Jones Act of 1935. ch. 338, 49 Stat. 436, 7 U.S.C. 427. June 29, 1935.

United States Department of Agriculture Extension Service. (1986). The Cooperative Extension System Basic Charter.

United States Department of Agriculture, National Institute of Food and Agriculture (2022). Cooperative Extension History.

Appendix

The attached PDF has an appendix that provides information on extension services/programs featuring community and/or economic development programming.

Footnotes

1 The 1862 land-grant universities are institutions of higher education in the U.S. that are designated by a state to receive the benefits of the Morrill Act of 1862, with their missions to focus on the teaching of and research in agriculture and the mechanical arts. The Morrill Act of 1890 was passed with concerns over segregation in the former Confederate states and required these states to either create a land-grant institution for Black Americans or to provide evidence that race was not an admission criterion for their existing land-grant institutions. The Equity in Educational Land-Grant Status Act of 1994 further expanded the land-grant system to include tribal colleges in 13 states, primarily in the southwestern and midwestern U.S.

² While institutions within these five states may offer this type of programming, the authors could not find information regarding programming efforts on these institutions’ websites. Likewise, particular institution types (1862, 1890, and 1994) in other states may offer Extension programs that address the areas commonly considered to be included in ECD, but information regarding these efforts was not readily available.

Publication 3998 (POD-05-24)

By Alan Barefield, PhD, Extension Professor, Devon Mills, PhD, Assistant Professor, Rebecca C. Smith, PhD, Associate Extension Professor, and James N. Barnes, PhD, Associate Extension Professor, Agricultural Economics.

The Mississippi State University Extension Service is working to ensure all web content is accessible to all users. If you need assistance accessing any of our content, please email the webteam or call 662-325-2262.